|

Having a China Dream with

Joe Studwell

ChainLink: Joe,

please tell us a little about yourself.

Joe: Born in England, lived in Hong Kong, Beijing (8 yrs),

and I live in Italy now. I travel back and forth to China.

ChainLink: Do you still contribute to the Economist?

Joe: I haven’t written for the Economist or the Economist

Intelligence Unit since 1999, though I’m sure I probably

will again at some point. Joe: I haven’t written for the Economist or the Economist

Intelligence Unit since 1999, though I’m sure I probably

will again at some point.

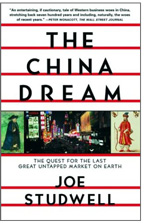

ChainLink: What made you write China Dream?

Joe: After eight years living in mainland China, I wanted

to figure out what I really believed about the place.

ChainLink: What made you start the China Economic

Quarterly?

Joe: I thought there was a niche for a very high quality

journal about the Chinese economy and investment in that

economy and I wanted to fill it.

ChainLink: From the beginning of global trade, business

people have dreamed of tapping into perceived large markets.

Yet both China and India have been elusive. The gold rush

is on, yet you are skeptical?

Joe: I’m skeptical about businessmen who think that

an economy, which is only the size of those of Spain and

the Netherlands combined is going to provide exponential

demand for their products and services. I’m enthusiastic

about businessmen who want to sell opportunistically to China

(as you would to any emerging market) and source cheap manufactured

goods from the place.

ChainLink: Joe, you talk about China’s two

economies: the so-called public government owned sectors

and the private

enterprise. Can you talk about what these are?

Joe: The government still controls at least

half of all economic activity in China. State companies dominate

in construction,

heavy industry and services—like telecoms and finance.

Doing business with the state is difficult, bureaucratic,

time-consuming and subject to huge swings in demand. It’s

tough to win in this area. On the other hand, the emerging

domestic private economy and the export processing economies

are highly competitive and profit-driven, while demand is

much less volatile. This is where it makes sense to do business. Joe: The government still controls at least

half of all economic activity in China. State companies dominate

in construction,

heavy industry and services—like telecoms and finance.

Doing business with the state is difficult, bureaucratic,

time-consuming and subject to huge swings in demand. It’s

tough to win in this area. On the other hand, the emerging

domestic private economy and the export processing economies

are highly competitive and profit-driven, while demand is

much less volatile. This is where it makes sense to do business.

ChainLink:

How is a businessperson to sort out who/what he is dealing

with in these two economies?

Joe: You have to constantly ask where the money is coming

from in any particular business—from public or private

demand. It’s not that difficult to do if you apply

common sense. What you must not do is wander around the place

wide-eyed, mesmerized by construction activity that is paid

for through a nationalized and insolvent banking system.

To think only with your eyes in China will not tell you where

real, profitable business activity is.

ChainLink: I like the fact that you have significant

focus on the trials and tribulations of starting a business

in

the China market. I asked Richard Chenevix-Trench[1] about

these investments gone sour and some firms leaving China.

His comment

was, that it just takes time—lots of time. My rebuttal

was, "So, that should be considered a market research investment?[2]" .

He agreed. Do you see companies staying the course, or will

more throw in the towel on trying to

crack this market?

Joe: It’s a very difficult market and so it takes

more time to fathom than most. On top of this, the domestic

market is exaggerated in most people’s minds, so it’s

unusually competitive. But capitalism never gives up; it

just keeps trying. Right now, foreign companies in China

are doing better than ever. This isn’t to say they

are meeting their original expectations, but performance

is improving—from a very low base. The Chinese government

is helping out with a relentless deficit spending campaign

that began in the wake of the Asian financial crisis and

means there’s lots of extra cash sloshing about. I

suspect foreign companies’ performance in the domestic

market will continue to improve for several more years, right

up to the point where China can no longer head off a horrendous

financial crisis. At that point, the local market won’t

look too pretty.

ChainLink: One thing you talk about, which kind of alarmed

me, is the lack of central control in the Chinese government.

With the fall of totalitarianism and the rise of the provincial

wheeler-dealer environment in China, is this cause for concern,

or good news for firms trying to operate in this environment?

Joe: There’s no shortage of control in China, it’s

just unpredictable who is exercising it from one moment to

the next—central government or provincial chiefs or

village gauleiters. The political system has not been reformed

one bit since 1979, so with all these new social and economic

pressures playing on it, it is very creaky, very spluttery,

very difficult for the businessman to figure out. The best

thing is to operate in a business where you can avoid the

politics.

ChainLink: From a supply source (components and other manufacturing

capabilities), I guess the future there is basically a low

risk issue? Costs are so low, and discipline high, it becomes

very difficult for contract manufacturers in other parts

of the world to compete. Are there supply risks that you

think we should be concerned about?

Joe: I think supply risks are pretty low. Currency risk

is negligible because the exporters earn foreign currency

and so won’t be bothered by problems in the domestic

financial system down the road. Labour unrest risk is rising

a little, but in my experience young Chinese women, for instance,

think that working on a production line is a dream compared

to a life of cashless misery tending fields in the countryside.

Logistical risk is low because export processing is coastal,

and there are loads and loads of functioning mainland container

ports these days. Of course it is wrong to assume China will

make “everything.” At the bottom end, activity

like shoemaking has already migrated away to a significant

extent to Vietnam and Bangladesh. China is taking over a

lot of stuff from richer Southeast Asian nations, but there

are plenty of areas where China does not compete so well.

China is not, for instance, hollowing out the semiconductor

industry in the Philippines (which is instead a huge supplier

to China) or the software services industry in India.

ChainLink: Many of ChainLink’s customers have

big Intellectual Property problems as well as outbound

trade

issues (border crossing regulations, etc.) Do you see the

Chinese getting their act together on this?

Joe: I think the Chinese government will get tougher on

IPR infringements as they affect more Chinese companies,

which is beginning to happen. But it will be very slow. I

also think the IPR issue is mainly an issue of counterfeit

exports. In the domestic market, it’s just not true

to say that every Chinese who buys fake Microsoft software

or a fake Gucci handbag would or could shell out for the

real thing if piracy was eradicated. This is a poor country—US$1,000

GDP per capita. So when you hear that hundreds of millions

of dollars of Viagra sales are being lost because there are

50 fakes on the market, you should take it with a pinch of

salt.

ChainLink: Chinese are big savers—verses Americans.

I assume their savings are helping to fuel the investments

in these growing firms, like the Japanese did. Would China,

though, wind up with a crisis like Japan once they have a

convertible currency, which will lead to inflation?

Joe: Chinese people’s savings, gobbled up and lent

out by the nationalized banking system, are paying for all

those fancy high-rises. There won’t be a convertible

currency prior to a financial crisis because it would expose

the bankruptcy of the current financial system. So, all those

American politicians who are calling for one because (in

the short term) the renminbi is undervalued, are wasting

their time. But I guess they have to campaign about something—there’s

an election due.

ChainLink: Joe, this is fascinating stuff! Do you

have some advice, words of wisdom to our readership? (Readers

are composed

of software firms, SC exec’s—both manufacturing

and logistics, US Department of Defense Logistics, some financial

investors, and my mother, of course!)

Joe: Common sense. In general, there’s a correlation

between big multinationals in China with big dreams and “visionary” CEOs

and losing money, versus smaller foreign entrants that can’t

afford to waste cash that turn out successful. It’s

a place where you have to roll up your sleeves and get very

involved. That means finding the best possible local managers

and then trusting them to get on with the job. Oh—and

don’t accept different standards in China. You are

there to make a profit, just like everywhere else, not to

listen to some guff about x thousand years of history. Remember

what the guy in the movie kept saying to Tom Cruise and you’ll

be ok: “Show me the money!”

ChainLink: Joe, Grazie!

Xièxie!

Merci! Dhanyavaad!

[1]

Hedge Fund manager at Sloane Robison Management

[2]

$2B plus for GM is a pretty big market research

investment!

©2003

ChainLink Research, Inc.

|